Programming Languages for LLMs: Are We Ready to Code for Machines?

When code isn’t just for humans anymore

Code wasn’t always meant to be read.

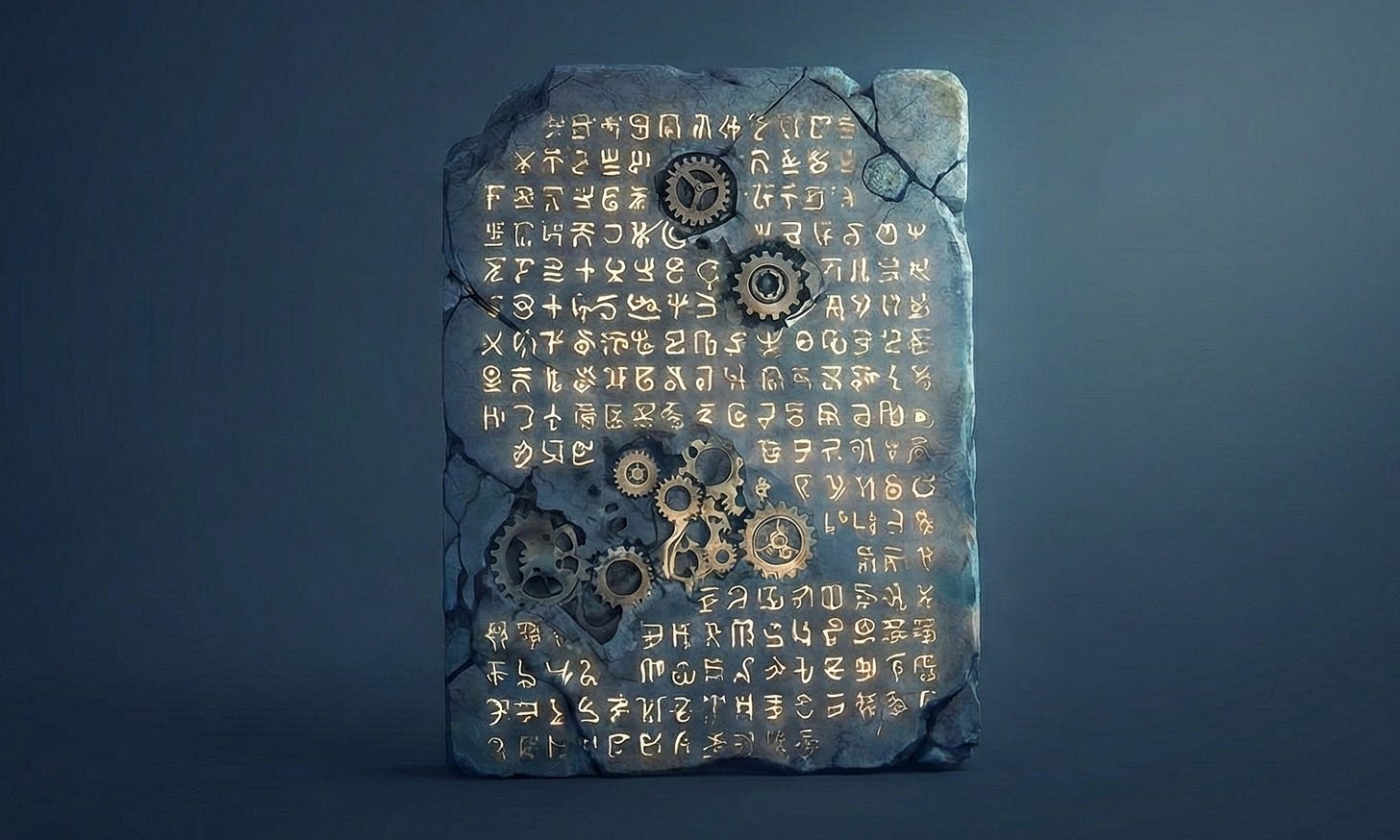

Before elegant syntax and abstractions, there was assembler. And before that, raw instructions spoken directly to hardware. Early programming wasn’t a shared language between people. It was a negotiation with machines. If we wanted something to happen, we had to bend our thinking to match theirs.

High-level languages changed that. They were an act of empathy, not for the machine but for us. As systems grew more complex, readability became essential. Code became something we could explain, review, and reason about together.

For decades, the primary reader of software was another human.

The New Reader

Now, a new reader has entered the room.

Large language models don’t just execute code. They read it, rewrite it, explain it, and increasingly maintain it. And they read differently than we do. Where humans rely on context, convention, and tribal knowledge, models rely on what is explicitly present.

They don’t fill gaps gracefully. They don’t assume intent unless it is stated.

That creates tension. Many features we value, like implicit behavior, dynamic patterns, metaprogramming, and subtle conventions, can confuse models operating with partial context. We can hold a mental map of an entire architecture, but models operate in windows. If intent is not local and explicit, the model hallucinates a bridge to nowhere.

Where we infer, LLMs must guess.

This is why explicitness, strong typing, and formal contracts are resurging. Languages like Rust or strictly typed TypeScript are not only safer for teams. They are easier for models to reason about. When a new kind of reader joins the conversation, clarity becomes a different kind of necessity.

From Implementation to Intent

This shift changes what programming actually is.

Historically, programming meant telling machines how to do things, step by step, line by line. But LLMs are increasingly capable of determining the how, as long as we are precise about the what.

Our focus moves from implementation to intent.

In this world, the most important thing we write may not be an algorithm, but a clear expression of outcomes, constraints, and assumptions. Tests become more than safety nets. They become executable intent. Documentation stops being an artifact and becomes part of the system.

Not free-form natural language, and not rigid code either. Instead, something in between. A structured, constrained way of saying this is what we want, this is what matters, this must never break.

The Contract Language

It is not hard to imagine what comes next.

We can picture a language where a service is not defined by its control flow, but by its guarantees. A module begins not with imports, but with declared intent. What it is responsible for, what constraints it must respect, and what “correct” means in observable terms.

We can imagine a function body with no logic. Only a strict return schema and a detailed contract, where the compiler is a model resolving the implementation at runtime.

Such a language would not look like Python or Rust. It would read closer to a formalized contract written in constrained natural language, backed by executable specifications and verification hooks. We define the space of valid behavior. The machine explores it.

The Architecture of Intent

This raises a practical question. When the machine writes the implementation, what do we actually read? And how do we debug it?

The codebase splits into two layers: the Source and the Artifact.

The Source is what we touch. It looks less like a recipe and more like a legal agreement fused with a test suite. It is concise, high-level, and explicit about what must happen.

The Artifact is what the model generates. It is verbose, defensive, and heavily instrumented code, perhaps in Python or WebAssembly, that actually runs. We will rarely inspect it, just as we rarely debug assembly unless we are desperate.

Debugging shifts from inspecting state to inspecting reasoning.

When a bug occurs, for example a payment is approved when it should be declined, the code will likely be syntactically perfect. Instead of stepping through lines, we examine a Decision Trace: observed user flag, referenced policy, overridden constraint based on ambiguous precedent.

The bug is not in syntax. It is in ambiguity. We do not fix it by editing generated code. We fix it by tightening the Source contract.

The Death of Refactoring

This separation implies the end of refactoring as we know it.

Today, code is an asset we polish and maintain. In this future, implementation code becomes disposable.

To optimize a module, we do not rewrite functions. We adjust constraints in the Source and regenerate the Artifact. Throwing away ten thousand lines of code costs nothing. Technical debt in implementation disappears. Intent debt remains, in the form of imprecise definitions that no longer match reality.

Our tools will need to evolve. A traditional git diff becomes meaningless when a tiny change rewrites an entire file. We will need version control for meaning, not text. The pull request of the future will not ask us to review code. It will ask us to review simulations of intent.

The Human Shift

Our roles will change as quickly as the tools.

For decades, a Senior Engineer was someone who knew the deep corners of a standard library. That skill is depreciating. The new Senior Engineer is an ambiguity hunter.

Their strength is not syntax. It is systems thinking. They spot the edge cases a model would misinterpret. They express complex systems in constraints so tight that misunderstanding becomes impossible.

Security shifts as well. Vulnerabilities will not only be buffer overflows. They will be psychological. Attackers will not break the stack. They will try to persuade the model to ignore its constraints. Security becomes adversarial semantics.

The Prediction

I predict that within the next few years, languages designed explicitly for collaboration between humans and LLMs will emerge. Most will fail. One or two will quietly succeed, and they will redefine what good code means. It will become less implicit, more explicit, and more intent driven.

These are only a few of the changes LLMs will bring to the software development lifecycle. From design to testing, deployment, and maintenance, nearly every stage will be affected as models participate in reading, generating, and maintaining code. The examples we discuss here illustrate the broader transformation, but the full impact is likely to be much wider and still emerging.

This will not happen only because such languages suit machines. It will happen because incentives align. Vendors gain tighter integration and lock in. Developers gain predictability and a shared vocabulary for human-machine collaboration.

Assembler gave way to C. C gave way to Python. Python may give way to something that looks less like a language and more like a contract, a shared understanding between humans and machines.

This change will not arrive with fireworks. It will arrive as relief, as clarity, as a system that simply works alongside us.

Only later will we realize that we have crossed a line. We will have moved from programming machines directly to programming intent in systems that think with us.